Series 4: The Culture Series

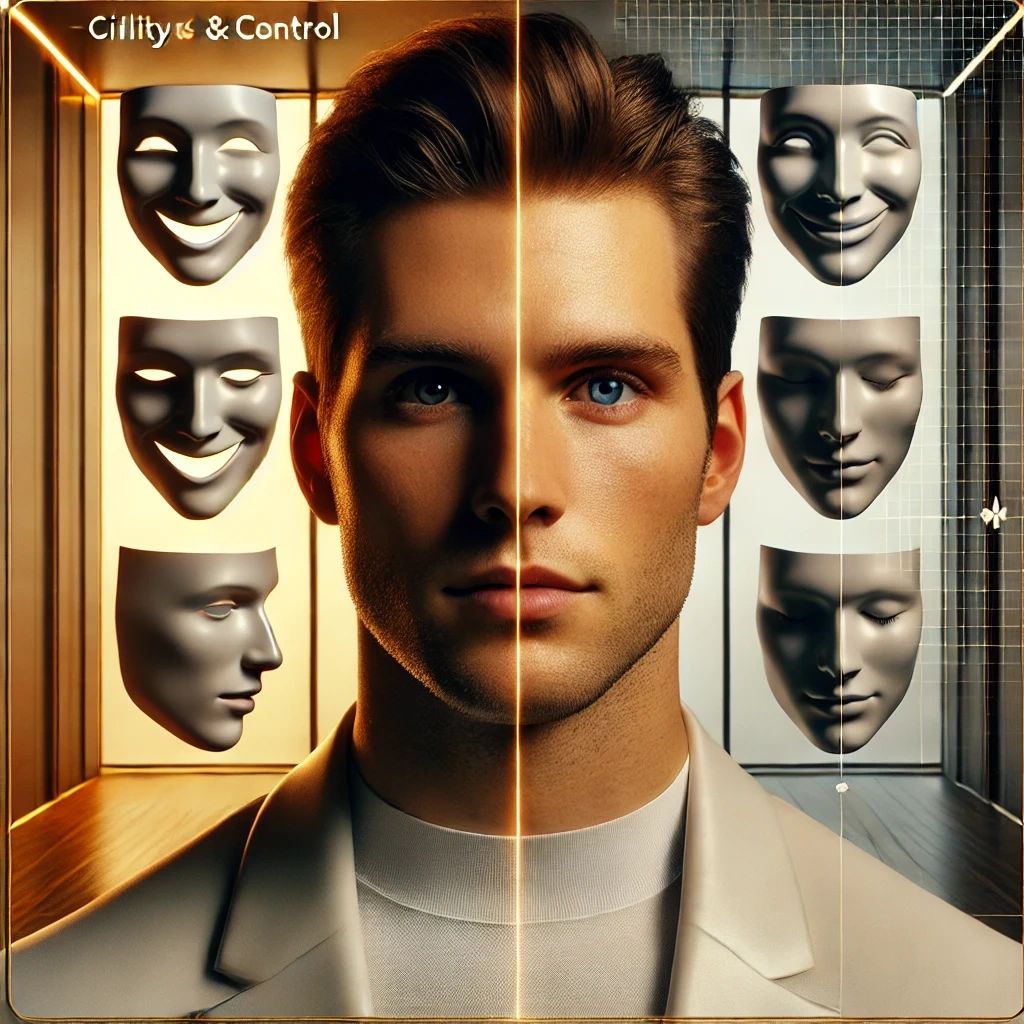

Civility & Control

When Niceness Becomes a Weapon

“When silence wears a smile, it’s harder to call it out.”

Control doesn’t always shout.

Sometimes it whispers: “Be polite.”

Sometimes it smiles: “Let’s not make this political.”

Sometimes it hides behind words like respect, professionalism, or maturity.

This is what happens when niceness becomes a strategy of control.

In workplaces, families, communities — and even queer spaces — civility is often used to silence truth, maintain comfort, and punish authenticity.

It’s not about kindness. It’s about compliance.

This episode explores how politeness can become a social leash — and why reclaiming your voice isn’t “rude,” it’s revolutionary.

2: The Culture of Niceness

“When we confuse silence with grace, we protect the wrong people.”

We’ve built a world that prizes appearances over integrity.

A world where the tone of a message matters more than its truth.

Where saying “that’s not very nice” is more effective at shutting people down than any open threat.

Civility culture tells us:

- Don’t be so emotional.

- Don’t make this about identity.

- Be the bigger person.

But let’s be honest — who benefits when the oppressed stay polite?

When minorities are told to tone it down?

When victims are asked to forgive “with grace”?

Niceness is often just control wearing perfume.

And in queer life, it can sound like:

- “You’d be more accepted if you weren’t so flamboyant.”

- “We support you, just don’t shove it in people’s faces.”

- “Not everything has to be about being gay.”

When comfort becomes the standard, truth becomes the enemy.

“Civility without honesty is manipulation in drag.”

The Culture of Niceness: When Civility Silences Truth

“When we confuse silence with grace, we protect the wrong people.”

In modern social life, niceness has become a kind of moral currency — a sign of refinement, diplomacy, and self-control. Yet beneath its polished surface, the culture of niceness often serves to maintain hierarchies rather than heal them. We live in a world that prizes appearances over integrity, where the tone of a message matters more than its truth.

This essay examines how civility, when detached from sincerity, becomes a tool of compliance. Drawing on the work of Audre Lorde, Sara Ahmed, and Michel Foucault, The Culture of Niceness explores how the demand to remain “pleasant” sustains systems of dominance and emotional suppression — particularly in queer life, where authenticity has always been a form of risk.

Civility as Control

Niceness has long been coded as virtue. It suggests grace, composure, and moral strength. But in practice, it often functions as control wearing perfume — a means of disciplining emotional honesty in favor of social harmony.

Civility culture teaches us to smooth over discomfort:

Don’t be so emotional.

Be the bigger person.

Not everything has to be about identity.

Such directives appear benevolent, but they work to protect the comfort of the privileged rather than the dignity of the oppressed. As Sara Ahmed argues in The Cultural Politics of Emotion, emotions that disturb the social order — anger, grief, resistance — are often framed as “bad feelings,” pathologized rather than heard. The result is a form of emotional policing disguised as moral virtue.

The Queer Demand for Politeness

For queer people, the culture of niceness has deep historical roots. It echoes the unspoken rules of assimilation: You’ll be accepted if you behave.

This translates into everyday microdisciplines — softening one’s tone, straightening one’s wrist, quieting one’s truth.

“You’d be more accepted if you weren’t so flamboyant.”

“We support you, just don’t shove it in people’s faces.”

“Not everything has to be about being gay.”

Each of these statements masks control as concern. They echo what Michel Foucault described as the disciplinary gaze — the subtle power that shapes behavior not through force, but through social conditioning. In this sense, niceness is not just an individual trait; it’s an institutional expectation, one that keeps marginalized voices palatable for mainstream consumption.

When Grace Becomes Gaslight

The rhetoric of grace — forgive and move on, be kind, rise above — is often weaponized against those who speak uncomfortable truths.

When victims are told to “forgive with grace,” when activists are told to “calm down,” when anger is treated as immaturity rather than insight, we confuse civility with moral superiority.

Audre Lorde’s essay “The Uses of Anger” remains a vital counterpoint: “Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against those oppressions.” Anger, for Lorde, is not the opposite of grace — it is grace in motion, the soul insisting on its right to feel and to be heard.

In queer and feminist contexts alike, the demand for niceness functions as a silencing mechanism. It prioritizes tone over truth, compliance over consciousness, and politeness over progress.

“Civility without honesty is manipulation in drag.”

The Difference Between Kindness and Compliance

Kindness is relational — it moves outward, rooted in empathy and care.

Niceness is performative — it moves inward, preoccupied with self-image and social approval.

The distinction matters because communities built on niceness mistake avoidance for harmony. In queer culture, this can manifest as toxic positivity: the insistence that everything must be fabulous, that vulnerability is weakness, that critique spoils the vibe. But true belonging is forged not through suppression, but through shared truth-telling — even when it’s uncomfortable.

bell hooks reminds us in Teaching to Transgress that education, love, and liberation are not polite processes. They are inherently disruptive. The work of healing and justice requires confrontation — not cruelty, but courage.

Conclusion

The culture of niceness teaches us to equate civility with goodness, but queer history reveals a deeper truth: progress has never been polite. Pride began not with decorum, but with defiance.

To dismantle systems that thrive on silence, we must learn to tell the truth even when it trembles. This is not a rejection of grace, but a reclamation of it — grace that makes space for honesty, that refuses to protect power at the expense of people.

Kindness heals. Niceness hides.

One builds bridges; the other builds barriers.

When comfort becomes the standard, truth becomes the enemy.

Learning the difference between the two is how we begin to speak — and live — freely.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge, 2004.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books, 1995.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press, 1984.

3: Tone Policing & the Myth of Respectability

“Politeness was never meant to protect truth — only power.”

Tone policing is one of the subtlest — and most powerful — forms of control.

It redirects the focus from what is being said to how it’s being said.

You speak about injustice — and someone says you’re “angry.”

You express pain — and they call you “too sensitive.”

You set a boundary — and suddenly you’re “rude.”

Sound familiar?

This is how social systems — from workplaces to queer spaces — keep marginalized voices in check.

They reward composure, not clarity.

They praise diplomacy, not truth.

And they label authenticity as aggression.

The result?

Entire communities become fluent in emotional translation.

We learn to dress our truth in neutral tones so it’s easier to swallow.

We apologize before we even speak.

“You were never too much — you were just in a room that asked you to shrink.”

Tone Policing & The Myth of Respectability: When Politeness Protects Power

“Politeness was never meant to protect truth — only power.”

Tone policing is among the most insidious and invisible tools of social control. It shifts attention away from what is being said to how it is being said, reframing justified emotion as irrationality. Within this framework, composure becomes the moral high ground, and anger — particularly the anger of marginalized people — becomes evidence of instability or immaturity.

This essay examines how tone policing and respectability politics intersect to suppress authenticity, particularly in queer and other marginalized communities. Drawing on the work of Audre Lorde, Sara Ahmed, and Frantz Fanon, we’ll explore how “civility” becomes a mechanism for upholding the very hierarchies it claims to transcend — and how reclaiming emotional honesty can be a radical act of resistance.

The Mechanics of Tone Policing

Tone policing begins with redirection.

You speak about injustice — and someone says you’re “angry.”

You express pain — and they call you “too sensitive.”

You set a boundary — and suddenly you’re “rude.”

By shifting focus to delivery, tone policing diverts accountability away from systems and back onto individuals. It reframes resistance as incivility, demanding that those harmed by injustice express their pain in ways that comfort their oppressors.

Sara Ahmed, in The Complaint!, calls this “the management of affect.” Institutions, she argues, often measure legitimacy not by truth but by tone — privileging those who remain calm over those who reveal discomfort. As a result, those most affected by injustice are also those least allowed to speak about it authentically.

Respectability as a Survival Strategy

Respectability politics arose historically as a strategy of self-preservation: marginalized groups adopting the behavioral codes of dominant culture to gain safety or acceptance. In Black, queer, and feminist histories, it was a form of “cultural armor,” a way to survive within spaces that viewed one’s very existence as deviant.

Yet, as Frantz Fanon notes in Black Skin, White Masks, assimilation through decorum often reinforces the very hierarchies it seeks to escape. To be seen as “respectable” is to be granted conditional humanity — one that can be withdrawn the moment emotion exceeds expectation.

In queer life, this dynamic echoes in statements like:

“You’d be more accepted if you weren’t so flamboyant.”

“We support you — just don’t make everything about being gay.”

Such remarks present compliance as civility, mistaking conformity for class and restraint for virtue.

Emotional Translation and Self-Editing

Tone policing’s greatest success is internalization. Over time, entire communities become fluent in emotional translation. We learn to repackage anger as sadness, conviction as curiosity, truth as tolerance.

We preface statements with apologies — “I don’t want to sound harsh, but…” — to make our honesty easier to digest. We moderate our tone not because we lack clarity, but because we’ve learned that clarity comes at a cost.

This dynamic mirrors what Audre Lorde describes in “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” Silence, she writes, is not safety but death; speaking, even when trembling, is the first act of liberation. The danger of tone policing is that it convinces us that muting our message is maturity — when in truth, it is the slow erosion of self.

“You were never too much — you were just in a room that asked you to shrink."

Queer Expression and the Burden of Performance

In queer spaces, tone policing often disguises itself as “progressive decorum.” Anger is labeled divisive; flamboyance is called performative; critique is deemed ungrateful. The queer person who demands more than tolerance — who insists on transformation — risks being dismissed as “problematic.”

This tendency reveals what José Esteban Muñoz describes in Disidentifications: the queer subject’s constant negotiation between assimilation and authenticity. Politeness becomes the currency of belonging, yet it exacts a psychological tax — the quiet exhaustion of perpetual moderation.

To resist tone policing, then, is not to reject dialogue but to reclaim full emotional range as a valid register of truth. Anger, grief, and passion are not moral failings; they are evidence of care. They signal that we still believe change is possible.

Reframing Politeness and Power

When we examine the social function of politeness, we see that it was never designed to protect honesty — only hierarchy. Politeness maintains appearances. It ensures that discomfort flows downward, not upward; that those in power remain undisturbed while those without power remain palatable.

True respect is not about tone but about listening.

True maturity is not about calmness but about courage.

True dialogue begins not with composure but with curiosity.

Tone policing masquerades as moral instruction but operates as censorship. Its antidote is not aggression, but authenticity — speech that refuses to contort itself for approval.

Conclusion

Tone policing and the myth of respectability are not merely social irritations; they are instruments of power that shape whose truths are heard and whose are silenced. For queer people — and for anyone living at the margins — the demand to “say it nicely” has often meant “say it less.”

Reclaiming voice is not about abandoning grace but about redefining it. Grace that silences is complicity; grace that liberates is honesty in motion.

Anger can be sacred.

Emotion can be evidence.

And politeness, when weaponized, is not kindness — it is control.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Complaint!. Duke University Press, 2021.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann, Grove Press, 1967.

Lorde, Audre. “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press, 1984.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

4: The Empathy Trap — When Compassion Becomes Compliance

“When empathy means self-erasure, it’s not empathy — it’s fear.”

Empathy is sacred. But it’s also been weaponized.

In a culture obsessed with appearing “good,” we often mistake people-pleasing for compassion.

We call it understanding — but really, we’re self-censoring.

We call it being considerate — but really, we’re absorbing everyone else’s discomfort.

For queer folks especially, empathy can become emotional labor:

- Soothing straight fragility.

- Educating without end.

- Being the “reasonable” one in every room.

But here’s the truth: empathy without boundaries isn’t healing — it’s self-abandonment.

And “niceness” that asks you to minimize your truth isn’t love — it’s manipulation.

When was the last time you said “it’s fine” when it wasn’t?

Whose comfort were you protecting?

The Empathy Trap: When Compassion Becomes Compliance

“When empathy means self-erasure, it’s not empathy — it’s fear.”

Empathy is among the most sacred capacities we possess — the ability to attune to another’s inner world, to imagine pain without needing to inhabit it. But in a culture obsessed with appearing “good,” empathy is often distorted into a performance of virtue. We call it compassion, but it frequently masks compliance. We call it care, but it often conceals fear.

For queer people, whose survival has long depended on emotional intelligence, empathy can easily become overextension — a habitual softening to make others comfortable. In such contexts, empathy transforms from a bridge of connection into a tool of self-erasure. As Brené Brown and bell hooks have both suggested in different ways, love and empathy without boundaries collapse into servitude.

This essay explores how empathy becomes a trap when it is decoupled from self-respect, and how reclaiming boundaries is essential to authentic compassion.

The Socialization of Self-Erasure

From a young age, many queer people learn that their emotional safety depends on others’ approval. We develop hyper-attunement — the ability to sense mood shifts, anticipate rejection, and regulate our presence to minimize discomfort. What begins as survival becomes habit: a form of social intelligence honed in environments that demanded performance over authenticity.

This mirrors what psychologist Carl Rogers called conditions of worth — the belief that love must be earned through compliance. For queer individuals, especially those raised in heteronormative or religious contexts, empathy becomes both shield and shackle. We learn to translate our needs into palatable language, to offer understanding before we are understood, and to apologize for existing too loudly.

In this way, empathy becomes less about connection and more about control — not of others, but of ourselves.

Empathy as Emotional Labor

Empathy, when practiced without reciprocity, mutates into unpaid emotional labor. In queer experience, this often takes familiar forms:

- Soothing straight fragility.

- Educating without end.

- Being “the reasonable one” in every room.

This dynamic parallels what Sara Ahmed describes in The Cultural Politics of Emotion: marginalized individuals are expected to manage the emotional equilibrium of dominant groups. Queer people often absorb discomfort in order to maintain peace — a peace that comes at the expense of truth.

The result is exhaustion disguised as grace. We call it understanding, but really, we’re self-censoring. We call it consideration, but really, we’re absorbing everyone else’s projections.

When empathy requires silence, it ceases to be empathy; it becomes complicity.

The Myth of the “Good Queer”

The empathy trap is closely tied to the myth of respectability — the expectation that queer people must prove their humanity through politeness, patience, and pedagogy. This “good queer” narrative rewards composure and punishes confrontation. It asks us to make others comfortable with our pain, to translate our trauma into lessons for those who caused it.

This pattern echoes the broader politics of tone policing, where emotional expression is deemed unprofessional or irrational. The more measured we are, the more seriously we are taken — but also, the more distance we create between our truth and its full expression.

bell hooks, in All About Love, reminds us that love cannot exist without justice. Empathy that demands our silence is not virtue — it is a form of emotional colonialism.

Boundaries as Radical Compassion

True empathy does not require endless availability.

True compassion does not mean absorbing harm.

Boundaries are not barriers to connection; they are the frameworks that make genuine care sustainable. They prevent empathy from becoming extraction — the slow leaking of selfhood into the service of others’ comfort.

When we practice boundaries, we replace people-pleasing with presence. We can listen deeply without losing ourselves, and love without surrendering authenticity. This shift transforms empathy from appeasement into agency.

As psychotherapist Nedra Tawwab writes in Set Boundaries, Find Peace, “The capacity for empathy expands, not shrinks, when we learn to include ourselves in its circle.”

Reclaiming Empathy as Power

To reclaim empathy is to reclaim power. It means recognizing that understanding others does not require betraying oneself. It means refusing to equate compliance with kindness.

For queer people, this reclamation is a collective act of healing. When we stop cushioning the world’s discomfort, we make room for truth to do its work — uncomfortable, yes, but liberating.

Ask yourself:

When was the last time you said “it’s fine” when it wasn’t?

Whose comfort were you protecting?

And what might change if your empathy began with you?

“Empathy without boundaries isn’t healing — it’s self-abandonment. Niceness that asks you to minimize your truth isn’t love — it’s manipulation.”

Conclusion

The empathy trap reveals a paradox at the heart of queer survival: the same emotional intelligence that kept us safe can also keep us small. But empathy was never meant to replace truth — it was meant to illuminate it.

When we pair empathy with integrity, compassion becomes liberation. We move from being mirrors of others’ emotions to being stewards of our own. And in that balance — between feeling and selfhood — empathy returns to what it was always meant to be: sacred, not sacrificial.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge, 2004.

Brown, Brené. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. Random House, 2021.

hooks, bell. All About Love: New Visions. William Morrow, 2000.

Rogers, Carl. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

Tawwab, Nedra Glover. Set Boundaries, Find Peace: A Guide to Reclaiming Yourself. TarcherPerigee, 2021.

5: The Emotional Cost of Being the ‘Good Queer’

“You can’t out-nice a system built to erase you.”

Queer people are often taught to earn safety by being pleasant.

To be the non-threatening one.

The palatable one.

The one who doesn’t make others “uncomfortable.”

But performing goodness for survival has a cost:

It disconnects us from our own anger, our own authenticity, and eventually — our own joy.

Politeness becomes a cage, not a bridge.

And what begins as emotional diplomacy ends as exhaustion.

It’s time to stop trying to be “good.”

Start being real.

“They said I was difficult. I was finally being honest.”

The Emotional Cost of Being the “Good Queer”

“You can’t out-nice a system built to erase you.”

From early childhood, many queer people are taught that safety must be earned. We learn to be agreeable, accommodating, and emotionally fluent — to soften our edges in exchange for tolerance. The result is what might be called the “good queer” persona: palatable enough to be accepted, articulate enough to educate, and careful enough never to offend.

This form of moral and emotional management, while often praised as maturity, conceals a deep psychic cost. As queer theorist Sara Ahmed writes in The Promise of Happiness, marginalized people are frequently asked to perform positivity in order to make others comfortable. But this performance comes at the expense of authenticity. The “good queer” becomes both diplomat and decoy — a figure who negotiates survival through self-suppression.

This essay examines the emotional labor of respectability within queer life, tracing how the pursuit of goodness can distance us from the very liberation we seek.

Respectability as Survival Strategy

The notion of respectability — the idea that marginalized groups can achieve safety through civility and compliance — has long been critiqued by scholars such as Audre Lorde and Michael Warner. Within queer contexts, it manifests as the pressure to appear “normal,” “nice,” or “non-threatening.” We are told, implicitly and explicitly, that acceptance depends on being digestible.

Many queer people learn to translate their identities into palatable terms: moderating voice, posture, or expression to avoid confrontation. This mirrors what psychologist Carl Rogers described as conditions of worth — the internalized belief that love and safety must be earned through performance. Over time, this conditioning creates a quiet violence: the constant monitoring of our own emotions in service of social peace.

To be perceived as “good” becomes a survival strategy — but it also becomes a prison.

The Anger We Were Taught to Suppress

Anger is often portrayed as incompatible with virtue, especially for those already marked as “other.” Yet anger, as Audre Lorde argued in her essay “The Uses of Anger,” is not destructive when rooted in clarity; it is transformative. For queer people, however, anger is frequently misread as hostility, defiance, or ingratitude.

To avoid punishment, we learn to internalize injustice — to turn outrage into over-explanation, critique into care, and boundary-setting into apology. In this emotional choreography, authenticity becomes dangerous, and politeness becomes a mask.

Over time, this chronic suppression fractures the self. We lose contact not only with our anger but also with our joy — because both emotions draw from the same well of aliveness.

The Performance of Goodness

The performance of being a “good queer” extends beyond interpersonal relationships into institutions, workplaces, and even activism. Queer identity becomes something to manage: presented in doses that others can tolerate. This reflects what Erving Goffman termed impression management — the constant regulation of self-presentation to fit social scripts.

In digital spaces, this dynamic intensifies. Social media rewards charisma, relatability, and “brand-safe” vulnerability — traits that translate emotional complexity into consumable content. The result is a paradox: a culture that celebrates authenticity while punishing those who practice it too honestly.

As José Esteban Muñoz reminds us in Disidentifications, queer survival often involves navigating the tension between conformity and resistance. The challenge is not to reject performance entirely but to reclaim it as expression rather than erasure.

Politeness as a Cage

What begins as emotional diplomacy ends as depletion. Constant self-editing drains the nervous system and fractures self-trust. We begin to equate quiet with safety, agreeableness with love, and restraint with strength. But these equations only reinforce the very hierarchies we hope to escape.

When politeness becomes the price of belonging, connection turns conditional. We may be invited into rooms — but only on the condition that we leave our fullness at the door.

As one queer writer poignantly observed, “They said I was difficult. I was finally being honest.”

To stop being “good” is not to abandon empathy or ethics; it is to reintroduce truth into the conversation.

Reclaiming Authenticity

Liberation begins when we stop performing for the comfort of those who misunderstand us. This reclamation is both personal and political. It requires the courage to disappoint, to be misunderstood, and to let discomfort do its work.

Authenticity does not mean perpetual confrontation — it means alignment. It’s the refusal to sacrifice integrity for approval. In this sense, honesty is not aggression; it’s self-respect.

bell hooks, in Teaching to Transgress, writes that genuine love cannot exist in the absence of justice. Likewise, genuine empathy cannot exist in the absence of truth. Being “nice” may earn us safety, but only authenticity earns us freedom.

Conclusion

The “good queer” is a product of systems that equate obedience with worth. To unlearn this conditioning is to risk being called difficult — but it is also to rediscover vitality.

Politeness without honesty is not grace; it is grief. The choice before us is not between kindness and defiance but between compliance and wholeness. When we choose to be real rather than agreeable, we trade applause for peace — and in doing so, we begin to live.

“You can’t out-nice a system built to erase you. Stop performing goodness. Start being real.”

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Promise of Happiness. Duke University Press, 2010.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday Anchor, 1959.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism.” Sister Outsider, Crossing Press, 1984.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Rogers, Carl. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

Reflection Exercise — The Civility Detox

“What if honesty was your new act of kindness?”

Take a moment to reflect on the last time you silenced yourself to seem polite.

In one column, write:

“What I wanted to say.”

In the next column, write:

“What I actually said.”

Now ask yourself:

- What emotion did I protect them from?

- What emotion did I suppress in myself?

- What would it feel like to speak the truth — calmly, clearly, unapologetically?

Civility isn’t peacekeeping. It’s people-keeping.

Start by keeping yourself.